Weaponry and Standards from the Malay World, illustrated by Albert Racinet

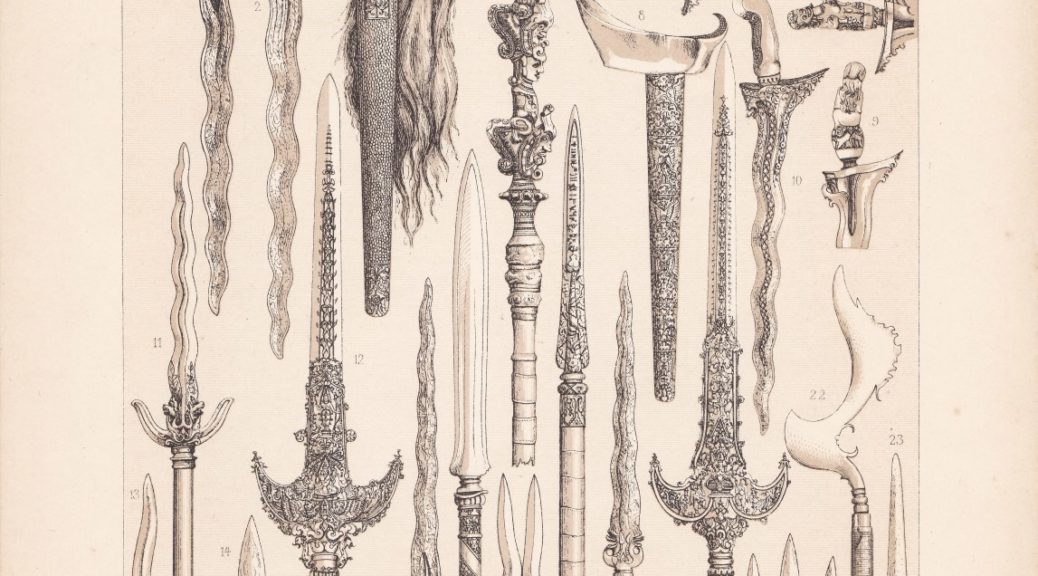

This plate is taken from Volume 3 of “Le Costume Historique” (1888), a series of volumes illustrated by French artist and costume historian Albert Racinet detailing dress and everyday objects from around the world.

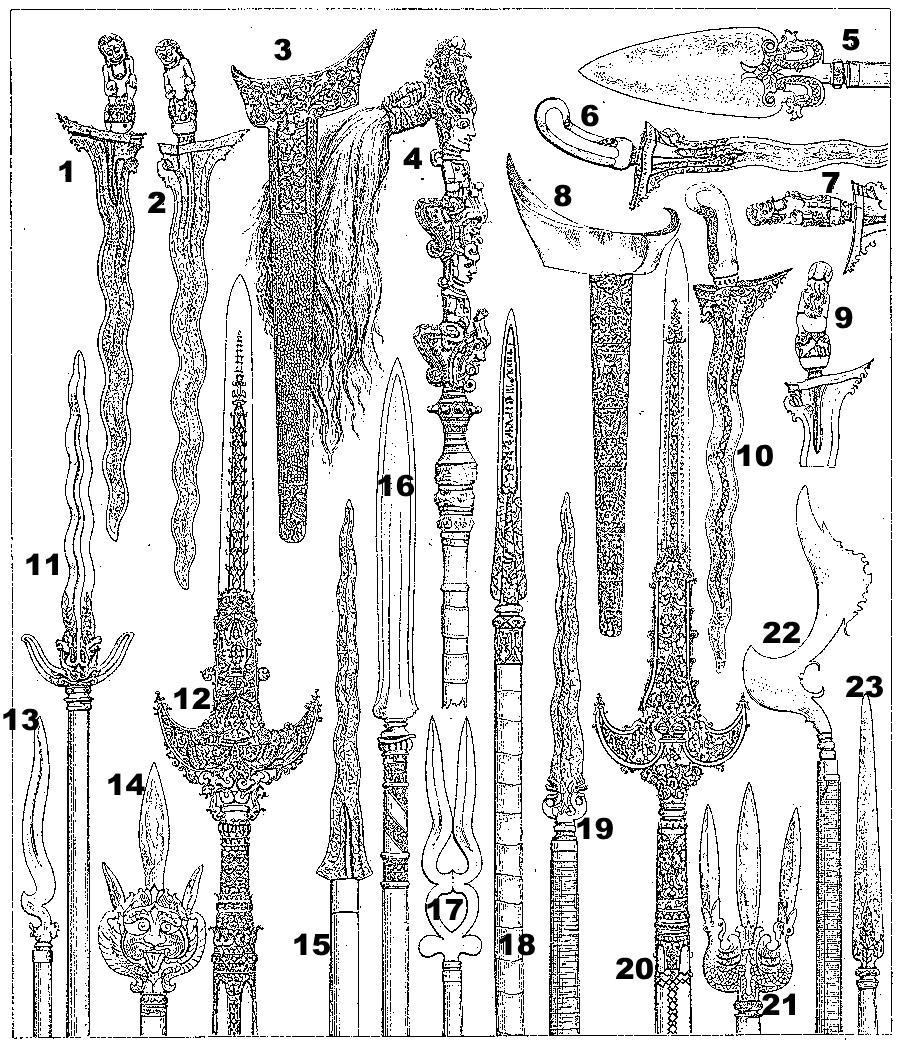

I have reproduced a scan of the plate below, as well as an outline that more clearly shows the numbering of the figures. I have translated the accompanying text into English, and provided scans of the original French so you can check my work.

(Translation note: the French word “Malaisie” in modern times is equivalent to current-day Malaysia. In the 19th century, however, it was a term originally proposed by French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville to describe the region currently comprising Malaysia, Indonesia and the Phillipines. I have chosen to translate “Malaisie” as “the Malay World” to avoid confusion with current-day Malaysia.)

The Asian Archipelago

The Malay World –Offensive Weaponry and Standards

Numbers 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 ,10 – Kerises with two scabbards

Number 4 – Standard

Numbers 11, 15, 16, 18, 19, 23 – Javelins, spears and halberds

Numbers 5, 14, 17, 21, 22 – More complex weaponry, of the same nature as the preceding items

Numbers 12, 20 – Indian spears

The Malay World includes the islands of the Philippines, the Moluccas, Celebes, Borneo, Sumatra, Java, Timor, etc. all inhabited by the Malays. It is a large section of Oceania, which is also known as the Asian Archipelago, Asia, or the Orient. The Malays, who occupy a considerable part of it, are regarded as the remnants of an ancient world that has collapsed.

In the Asian archipelago, their weapons bear the traces of their ancient civilisation. Today they are Muslims who nevertheless remember the Buddhism that they formerly practiced; the imagery that they like to invoke in the decorations that they use is proof of this, and without going to the isle of Bali to examine the impressive monuments from a time unknown to their Javanese ancestors, one can be assured by the simple inspection of the handle of a keris, representing some ancient idol, or the shaft of a standard with its billowing tail. The weapons of the Malay World, frequently constructed with the touch of a true artist, are sometimes produced with astonishingly inadequate resources, and those who manufacture them must do so with particular skill.

Dampierre, who in 1586 [1] was struck by the state of industry in Mindanao, an island in the Philippines, noted that the smiths there only had poor tools, and possessed neither vices nor anvils; they would hammer iron on a particularly tough stone or an old fragment of a cannon, and this did not stop them from producing finished works. In fact, the more ancient weapons are still considered to have been forged with a superior finish.

The Malay dagger, the keris, is a forward-projected weapon with a straight or a flamboyant blade; however it is also found with larger dimensions than usual where the two forms are combined and the rightmost edge undulates towards the point. The keris is sometimes poisoned with the sap of the Upas tree [2]. All free Malays always carry about their person this weapon which is forged with particular care; it is considered dishonourable to leave the house without it.

Three kerises are carried as part of military uniform: the first is acquired by the officer who carries it, the second passed down by his ancestors, and the third given to him by the father of his bride at the moment of matrimony. Two of these daggers are placed on each side of the belt, the third at the back; not counting the sword suspended on the left side by a sling. With the court uniform, where the shoulders, arms and the entire torso down to the belt are bared, a single keris is carried on the right side, and a knife, called the wedung [3], on the left.

There is not really any important distinction in the manner in which different classes carry the keris.

The handles are made from all sorts of durable materials – gold, silver, copper, ivory, ebony, white wood, carved or sculpted with finesse; sometimes they are even drilled; or still they are made very simply, from horn or plain wood, so that they sit well in the hand. The strong blades, generally made from a rough Damascus steel, are very hard and are more or less inlaid with gold or silver.

The scabbards or sheaths are often also finely crafted. Their large mouths are designed to retain the weapon in the belt, as they are not otherwise fixed. They are made from wood, inlaid with delicate ornamentation or covered with splendid fabric, metal layers or reptile skin.

The spears have long heads, straight or flamboyant, with sharp edges, reminiscent of the dagger blades; the socket may be deep or shallow. Among the damascening, one often finds inscriptions; the shafts are made of ironwood, plain without ornamentation, or of bamboo. Sometimes the upper part is enriched with an embellishment of copper or another metal covering the patterns. On other occasions, as with the shafts of the standards, it is enclosed in nailed-down ferrules, which contribute to the rigidity and form an alternating pattern. The damascening is of the same type as that of the keris: gold, silver, or simply engraved.

The other weapons with unique blades (numbers 5 & 13), with two points (number 17), or forked like a trident (number 21) or mounted like the jaws of some large animal, embody to different degrees the characteristics of our medieval fauchard [4] and mace, and at the same time resemble cut-and-thrust weaponry. Concerning the two Indian halberds, of which we have shown the entire upper parts, these are two of the most elegant and admirably carved weapons, and make one see that, by the firmness of their design and the richness of their decoration, the Malay artisans were only the students of those who created these beautiful forms. These two weapons have been in Europe since 1727.

(Pictorial documents from museums in Germany)

Notes:

[1]: a possible typo. An English explorer called William Dampier was a part of the crew of a ship that raided Minandao in 1686.

[2] Antiaris toxicaria, also known locally as the Ipoh tree, after which the capital of the Malaysian state of Perak is named. The sap is tapped much like rubber, and can be deadly once it enters the bloodstream.

[3] The wedung is a short,broad machete-like blade found on Java and Bali.

[4] The fauchard is a medieval European polearm with a curved blade, similar to the Japanese naginata or the Chinese guan dao.