Jim Hislop, Unconventional Soldier and the Last White Game Warden of Malaya (Part 2)

(Continued from Part 1 here)

Rumbles in the Jungle

After the war ended, Hislop returned to Scotland to convalesce. Naturally, he planned to return to his beloved Malaya as soon as possible, and hoped to finally trade in his role as a rubber planter for one as a game warden.

In April 1946 he once again took up residence in his old rubber estate. Ever keen to improve his junglecraft, he began to hear whispers and rumours, and saw for himself the signs of something brewing out there amongst the trees.

Malaya’s communist factions had been well-armed by the British during the war and were emboldened by their recent roles in ousting the Japanese from the Peninsula. A period of economic unrest followed the occupation, and the Malayan Communist Party now set their sights on controlling the colony for themselves.

Warnings from Hislop and others with their ear to the ground went unheeded by the authorities, and on 6th June 1948, at Sungei Siput, Communist forces made the war public, killing three British planters. This was the first strike of the Malayan Emergency – labelled as such by the British government because plantation and mine owners would have received no insurance payouts for losses sustained during a “Malayan War”.

Hislop’s jungle treks had not gone unnoticed, and his knowledge of Communist movements clearly marked him as a threat. Enough of a threat that one night that August, at midnight, eighty-seven guerrillas crept out of the rubber trees with their sights set on Jim Hislop’s bungalow.

The opening salvo from a Bren gun was the first he knew of it. More bullets zipped right over him as he rolled off the bed, desperate to arm himself. With the aid of his trusty rifle, a pistol and six grenades, he held off his would-be assassins for an hour before making a break for it into the depths of the plantation. He ran for two miles to seek help from the nearest police station, leaving behind ten dead.

All this did not go unnoticed by the authorities either. The British were caught short by their lack of counter-insurgency capabilities at the beginning of the Emergency, and decided to capitalise on the large number of old hands from Force 136 and other wartime operations who were still present in Malaya.

Ferret Force was intended to fill the critical gap. This mobile jungle strike force formed units that teamed Europeans with wartime guerrilla experience with Malays, Gurkhas and aboriginal trackers. Hislop was selected to head up No. 4 Ferret Force, leading seventy-five men as a Lieutenant Colonel and taking the fight to the enemy in their own territory.

Ferret Force uncovered twelve Communist camps and killed 27 of their number, but in the end suffered the fate of many unconventional operations – that of being too politically sensitive. By the end of 1948 the Force was disbanded. Many of its members would take their experience into the Malayan Scouts, a forerunner to the re-established Special Air Service that would be resurrected a few years later.

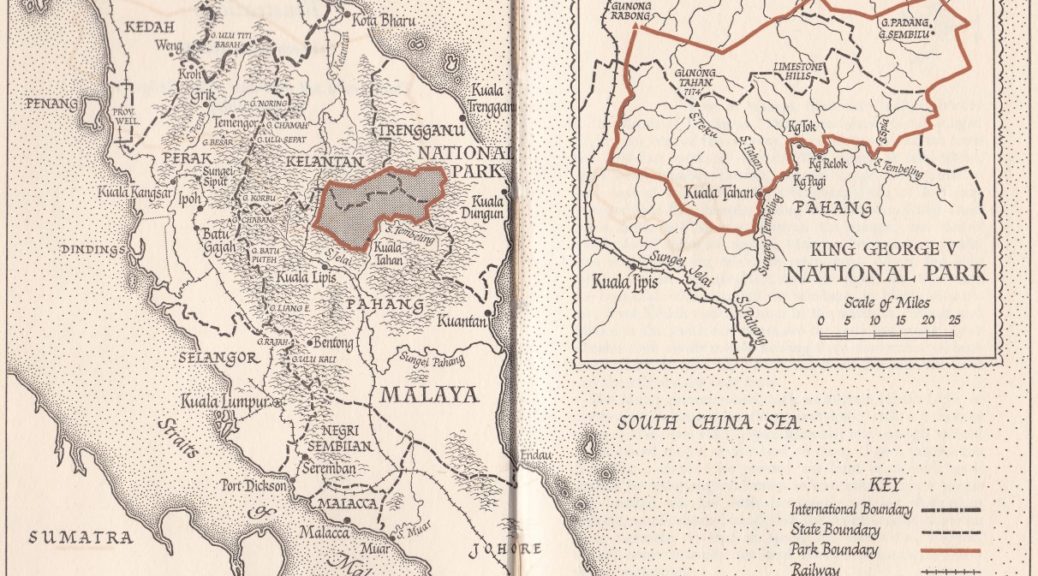

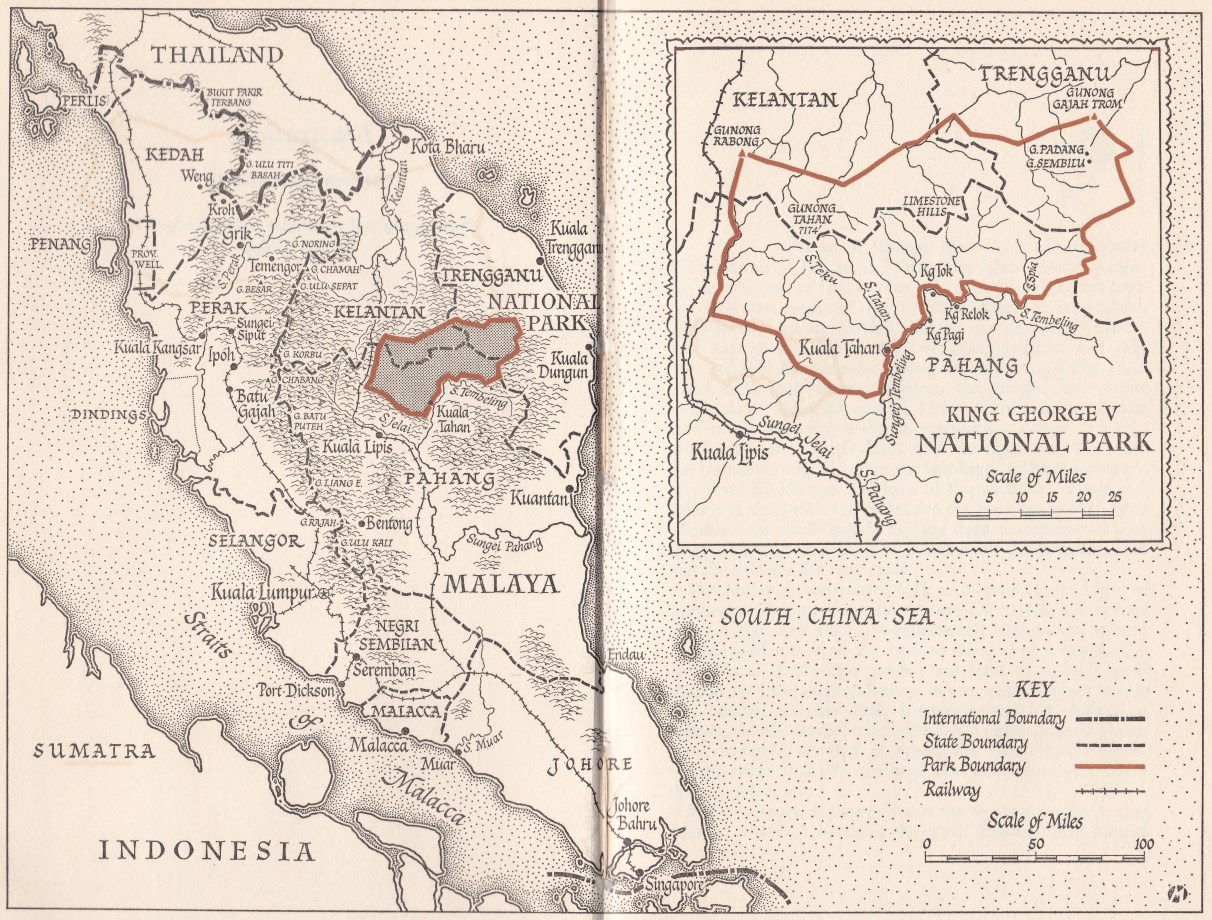

But this life was no longer for Jim. After hanging up his uniform for what he thought would be the last time, he joined the Malayan Game Department in 1949, finally beginning the life of his dreams as Game Warden of the state of Pahang and superintendent of Malaya’s Taman Negara National Park.

The Company of Animals

Hislop was later appointed as Game Warden of the state of Perak. Although no longer directly involved in the conflicts of the Emergency, his talents were still in demand. The Sultan of Perak had bestowed upon him the title of “Protector of Aborigines,” and the Army made full use of this. He was asked to recruit suitable bodies for the newly-formed Perak Aboriginal Areas Constabulary, the remit of which was to make contact with and befriend members of Orang Asli tribes such as the Temiar, Semai and Negritos. It was well-known that such tribespeople were a potentially useful source of information, but many had already been swayed to Communist support.

The PAAC was an attempt to turn the tide by utilising “winning hearts and minds” strategies, which were made famous a decade later by the SAS in Borneo. The unit was eventually compromised, and demobilised in 1952 after three officers and several tribal headmen were killed by the enemy.

During this time Jim Hislop also got married, a feat which many of his acquaintances would have considered more preposterous than any of his exploits with Force 136. In 1951 a tall, beautiful English girl walked into his regular watering hole and he announced “That’s the girl I’m going to marry.” No doubt the laughter from his drinking companions was uproarious, but just a few months later Jim and June honeymooned in Hong Kong.

Hislop also found time to assemble one of the finest butterfly collections in Malaya, which at the time of Ronald McKie’s book research visit encompassed 950 of the 1100 known Malayan species. Third time was the charm – his first collection fell to the Japanese invasion and his second to Communist gunfire during that near-lethal night on the plantation in 1949. His name was even immortalised in the annals of lepidoptery – Ethope diademoides hislopi was officially recognised by British Museum butterfly expert A. S. Corbet as a new species.

As his personal life expanded, so did his career. In 1957, the year of Malaya’s independence, he was appointed to the post of the country’s Chief Game Warden. His was the impossible task – balancing the protection of human life, property and animal welfare. Nothing threatened to tip these precarious scales more than Gajah, the Malayan elephant.

Shrinking jungle habitats led to raiding of estates and villages for food, and so man and elephant became locked in a circular conflict. Elephants are hard to kill, and wounded elephants only become more dangerous. They also seek revenge. Hislop became an expert tracker and dispatcher of rogue Gajah, and yet never became comfortable with it.

In one particularly close call, typically understated in his diary (“Slipped and gun went off. Cow bolted. Followed but getting dark. Felt dreadfully ill.”) he tracked a herd all day through a thunderstorm, suffering from acute dysentery. Torn to shreds by thorns and covered in a viscous mixture of mud and fresh elephant dung, he took several unsuccessful shots at an old cow, who turned to charge. He tripped on a root and fell face down in the mire as his remaining barrel emptied itself. Only yards from him, his target skidded to a stop and finally decided to bolt. A three hour hike back through the dark awaited him after his near-death ordeal.

Hislop was often called upon to deal with another of the jungle’s most feared residents. Sir Stripes, His Lordship, The Old Gentleman – for the Malays considered it bad luck to use the true name of the tiger – was not as dangerous as Gajah. Occasionally one would become a man-killer, and when the protective magic of the local pawang (sorcerer) had failed, Hislop would find himself sat in a tree for one or more nights in a row.

McKie’s book details many other animals found in Peninular Malaysia. Jim Hislop was reportedly the first person to ever film, in colour, a herd of seladang, the Malayan wild ox now under threat of extinction. Whether this film has survived, along with Hislop’s diaries of his experiences with sun bears, binturongs, tapir, rhinos and many more, is unknown. The published extracts from his diaries also reveal that Hislop was the first known man to cut a path through the treacherous land route to Gunung Tahan, Malaya’s “Forbidden Mountain”, before climbing it and reaching the peak at 7168 feet.

Exodus

In 1959, at the pinnacle of his career, Jim Hislop was forced into retirement. After Malaya gained independence, government positions previously held by Europeans were relinquished to native-born workers. Withdrawing from his life in the jungle, he became a stockbroker in Kuala Lumpur – it is hard to imagine a profession less suited to a man of his talents.

Although he was still not far from the jungle, and spent much of his time volunteering his skills and expertise to the Game Department, the impact he was able to have on Malayan conservation and wildlife was much diminished.

While he was Chief Game Warden, despite the years of tenacity, hard work, and sheer drive to realise his dream, his attempts to create more reserves ultimately failed. His last effort before retirement, to have all forest reserves designated as game reserves, was rejected. Now, no longer a direct part of the system, he could only look on as deforestation, industrialisation and the loss of Malaysia’s natural treasures marched on.

Ronald McKie once asked Hislop if it would matter if the little remaining wildlife in the world was exterminated.

“For people content with hideous towns, spiderweb roads, advertising hoardings and dustbowls – no. For me, for many others, and for the long-distance future of man, it would be an international calamity and yet another proof that man is not as intelligent as the animals and not fit to inherit anything.”

In 1967 Jim Hislop returned to Scotland, then spent a couple of years as a forest surveyor in Indonesia, before returning to his homeland for the final time. He and his family settled in Pitlochry, and he turned his hand to woodworking. There he remained, ever the polymath, keeping active pursuits in bagpiping, Highland games judging, and fishing, until his death in 1992.

References:

Man who tamed the Malayan jungle, D.A. Macpherson, New Straits Times April 4 1992

Out in the Midday Sun: The British in Malaya 1880-1960, Margaret Shennan

The Company of Animals, Ronald McKie

One thought on “Jim Hislop, Unconventional Soldier and the Last White Game Warden of Malaya (Part 2)”