Jim Hislop, Unconventional Soldier and the Last White Game Warden of Malaya (Part 1)

In the 1930s the Malay Peninsula was almost entirely covered in jungle. Malaya, as the collection of British territories was known pre-independence, was a key producer of rubber. The rubber tree, indigenous to Brazil, grew just as well in the Far East and quickly rose to become one of Malaya’s key cash crops.

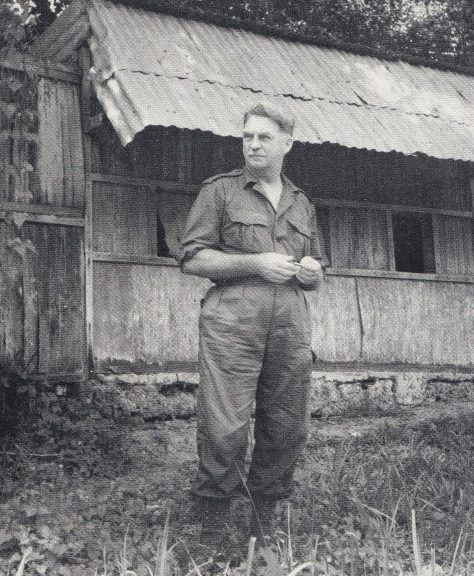

Rubber plantations dotted the peninsula. Employment on these large estates attracted workers from the UK and Europe, and it was as one of these transplants to the Far East that Jim Hislop first encountered the jungle. Malaya was seen as one of the cushiest colonial options for civil servants and workers alike, but Hislop’s extraordinary career would take him far beyond the planters’ insular world of afternoon tiffin and whisky sodas on the verandah.

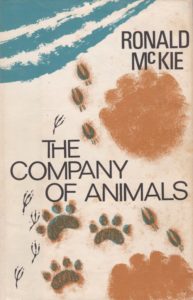

Much of the information for this article has been extracted from The Company of Animals (1965) by Ronald McKie. This book is part biography of Jim Hislop and part study of the ways of Malayan fauna. McKie was an Australian journalist and author who came to befriend Hislop and provided us with the only major source of information on his life.

Much of the information for this article has been extracted from The Company of Animals (1965) by Ronald McKie. This book is part biography of Jim Hislop and part study of the ways of Malayan fauna. McKie was an Australian journalist and author who came to befriend Hislop and provided us with the only major source of information on his life.

Descended from a long line of Scottish foresters, James Alexander Hislop began his life a world away from the heat and humidity of the Malayan jungle. Nevertheless, his outdoorsmanship started at an early age and prepared him well for his change in climes. He started his forestry career on the Earl of Moray’s estate on the shores of Loch Fitty in Fife, completed a diploma in forestry at Edinburgh Botanical Gardens, and then like so many young British men of the time, felt the call of the Orient.

The wanderlust may have been in his blood, as Hislop’s father left Scotland and his family for the even harsher Saskatchewan, making the trek across the Whitehorse Pass on foot during the Klondike gold rush. The rejection at such an early age imprinted itself on young Jim, and no doubt contributed to his neverending search for something greater.

In 1937 Hislop came to Malaya to start a new life as a junior rubber planter, securing a job on the Lukut Estate near Port Dickson on Malaya’s west coast. His upbringing stood him in good stead, gravitating naturally as he did to outdoor work and immersion in the natural world. The long days and hours on foot posed no problem to a man who felled his first large tree before the age of twelve and thought nothing of swimming through winter lochwaters while on a hunt.

It did not take long for Hislop to outgrow planter life. He began to learn more about the jungle around him, taking trips whenever he could to piece together knowledge about plants, animals and the ways of the locals. He began to dream of a career that would let him make a difference, to protect the inhabitants of his adopted new world.

Although he would eventually get his wish, the rumblings of war sidelined his new ambitions.

You Will Never Die Violently

Jim Hislop never wanted to be a soldier. In earlier life he had been rejected by the Royal Air Force due to a childhood accident that left him blind in one eye. Nevertheless, in 1939 he joined the local Volunteer Force. Even though Malaya was still considered safe at this time, half a world away from the relentless machinations of European fascism, he still felt the need to be prepared.

Ten months before Pearl Harbour and the Japanese invasion of the Malay peninsula and archipelago, his jungle experience led to selection for Border Patrol, a secret reconnaissance group that was tasked with investigating the Thai-Malay border. On these long treks he learned to build shelters, to read tracks and signs, to live off the land. On the Thai side of the border the group found trails already cleared in preparation for a coming invasion.

After the completion of this mission he served as a jungle scout and as a member of stay-behind commando group Dalforce. Following the fall of Singapore, he escaped to India on a steamer that was almost sunk by Japanese torpedoes. In India, he joined up with Force 136, the Asian offshoot of British Special Operations Executive. The ulterior motive, of course, was to find a way to get back to Malaya.

The first try involved an attempted landing by submarine, but hours of depth-charging from a Japanese destroyer put paid to that idea. Force 136 then tried their hand at paratrooping, and in February 1945 Hislop and five others dropped blind into northern Kedah to organise counter-insurgency operations among the Malayan Chinese Communist guerrillas. His efforts would later earn him the Military Cross.

Hislop’s journal during these rain-soaked, terrifying days and nights show that even when every jungle thicket could conceal sudden death by Japanese bullets, he was still a keen observer of nature.

March 14, 1945: Bright colour in jungle fruit is often a sign that it is poisonous. The animals, particularly monkeys and squirrels, and the jungle rats, won’t touch the gay clusters of fruit one often sees. Fruit ignored in an environment where everything eats everything else is fruit to be avoided. Learn from animals who know. It is a good jungle rule.

April 25: I was walking alone up a slippery slope on a game trail in heavy rain which destroyed all other sound. I didn’t know it but a full-grown tiger was coming up the slope on the other side. He couldn’t hear anything either. We met face-to-face at the top of the slope. I don’t know who was most surprised – me in a rotting uniform and a filthy beard out of which I’d just picked a few leeches, or the tiger. My instinct told me not to move and certainly not to run, although I wanted to run Instinct, reason, whatever it was, I stood perfectly still. The tiger recovered from his surprise, started at me for a good ten seconds, then snarled, showing his beautiful teeth, and slowly turned aside into the jungle and went off growling.

In August 1945 Jim Hislop emerged from the jungle, suffering from malaria and malnutrition, a survivor of more close calls than any one man should have to endure in his lifetime. But he was still alive. Several years prior at Lukut, after his first encounter with an elephant, the rubber estate’s Tamil first-aider examined the patterns on his arm and confidently predicted: “You will never die violently.” It was unlikely that anyone who knew him at the time would have agreed.

Read on with Part 2 here

2 thoughts on “Jim Hislop, Unconventional Soldier and the Last White Game Warden of Malaya (Part 1)”

Jimmy was a great friend of my father and mother during our time in Malaysia My father was c/o flying for the new Royal Malaysian Airforce. He played his highland pipes on our veranda in the evenings and took us into the jungle butterfly collecting. As a result there is a butterfly named after my father.

Dad wrote his obituary which was published on the Daily Telegraph